- About Us

- Advertise

- Editorial

- Contact Us

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

© 2025 MJH Life Sciences™ and Dental Products Report. All rights reserved.

5 injection techniques you need to master

Anesthesia failure is a common problem, but these techniques demonstrate great success.

As a dental hygiene educator and national speaker on the delivery of local anesthesia, I understand the ways in which our schooling has failed us. We spent countless hours during our semesters of hygiene school intimately studying the anatomical structures of boney and muscular landmarks while understanding the displacement of nerves and blood vessels of the head and neck. This studying was supposed to prepare us to understand anatomical considerations for our patients in the delivery of local anesthesia.

Additionally, dental hygiene school taught us a series of injection techniques that ultimately should serve all of our patients’ anesthesia needs. What I have learned from my time in speaking with experienced clinicians is that they realize the immense challenges noted with the blind delivery of local anesthetic. Generally speaking, providers utilize arbitrary landmarks in identifying a probable location of a nerve that may or may not be present, bifurcated, or provide accessory innervation. Additionally, we all realize that not all patients are innervated or structured the same way and these unique considerations provide subsequent challenges in the successful delivery of anesthesia.

Anesthesia failure, or the unsuccessful ability to achieve total and profound anesthesia, is a common occurrence in the provision of local anesthesia delivery. The frustrations experienced due to the excessive time, additional techniques, and questionable looks from our patients often diminish our confidence in the delivery of traditional anesthetic techniques.

Rest assured, as there are several alternative techniques available for the dental provider that utilize minimal anatomical considerations, demonstrate greater success, or simply require easier technique modifications.

This article focuses on the top five alternative injection techniques you need to review and master for your anesthesia delivery.

Click through the slides to see the techniques.

1. The Anterior Middle Superior Alveolar (AMSA) Nerve Block

As a dental hygienist who delivers block anesthesia primarily for scaling and root planing procedures, I often get countless questions from patients regarding my anesthesia technique. Patients want to know how many injections they’ll need, how long they’ll be numb, and they’ll question your technique if it isn’t impeccable.

Dental hygiene school taught me that maxillary quadrant anesthesia is best achieved through ASA, MSA, PSA, GP and NP injections, and after spending nearly half of my allotted SRP appointment time on anesthesia delivery and patients asking, “Another one?” I recognized my need to re-evaluate my anesthesia technique for maxillary pain control.

After realizing that patients don’t appreciate five individual penetrations (two of which being palatal injections) in one quadrant and recognizing that approximately 50 to 72 percent of patients don’t have an MSA nerve, I looked into alternative techniques to achieve maxillary anesthesia. Of note, many providers use the Infraorbital technique to minimize penetrations for the ASA and MSA blocks but still leave the patient with active sensations on the palate.

The Anterior Middle Superior Alveolar (AMSA) Nerve Block anesthetizes all maxillary nerves not anesthetized by the Posterior Superior Alveolar (PSA) Nerve Block. AMSA nerve blocks anesthetize the central and lateral incisors as well as the canines and premolars in addition to the periodontium from incisors to premolars on the facial tissues and incisors to molars on the palatal aspect.

This technique is performed by approximating an imaginary line between the two maxillary premolars on the side to be anesthetized and drawing this line down to the junction of the alveolar process and the palatal process. Needle penetration at a 45-degree angle into the palate and delivery of anesthetic upon gentle contact with bone permits the provider to observe appropriate blanching both anteriorly and posteriorly to ensure appropriate diffusion of anesthesia.

Delivery of anesthesia at the AMSA point of penetration maximizes diffusion of anesthesia through the palatal bone and into the maxillary dental plexus, providing both palatal and buccal anesthesia in the quadrant of choice.

Minimizing penetrations in the maxillary arch to the AMSA and PSA improves time management, increases patient appreciation, and ensures complete anesthesia to the maxilla.

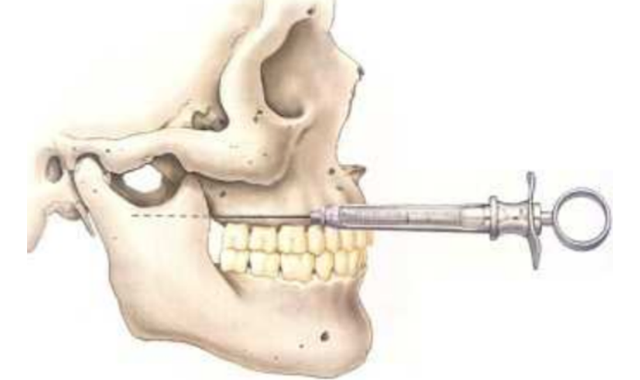

2. Gow-Gates

It’s with great bias that I share the details of the Gow-Gates Nerve Block technique. Admittedly, I haven’t delivered a true inferior alveolar nerve block for direct patient care since I graduated from dental hygiene school blah-blah-blah years ago. Sure, I would deliver an IA nerve block during my faculty days as a means of demonstrating the highly unsuccessful, incredibly controversial technique that countless graduates believe is the only means of achieving mandibular anesthesia.

While the inferior alveolar nerve block technique may provide adequate results for many clinicians, it also provides several challenges such as inconsistent anteroposterior location of the nerve, premature contact with bone, lack of boney contact, bifid and ectopic nerves, and multiple penetrations required to achieve unilateral anesthesia. In addition, the inferior alveolar nerve block holds a published failure rate of up to 31 percent of all injections, leaving the IA nerve block as among the highest failure rates in dentistry. Therefore, in at least one out of every three mandibular blocks that are delivered, anatomical obstructions or technique modifications require the clinician to consider alternative injection techniques.

A history lesson: In the 1970s, Dr. George Albert Edwards Gow-Gates, an Australian dentist, published about a 99 percent success rate approach to mandibular anesthesia. Considered a true nerve block, the Gow-Gates provides complete anesthesia of the mandibular nerve (V3).

The Gow-Gates nerve block provides anesthesia of the mandibular nerve as it travels through the pterygomandibular space prior to entry into the mandibular canal. Therefore, it anesthetizes not only the inferior alveolar nerve but also the mental, incisive, lingual, mylohyoid, auriculotemporal, and buccal nerves as well as all mandibular teeth to the midline on the side of choice. This provides multiple advantages such as requiring only one injection for unilateral delivery, a high success rate, and fewer post-injection complications.

The use of extraoral landmarks like the intertragic notch and the contralateral labial commissure, and intraoral landmarks such as the mesiolingual cusp of the maxillary second molar on the side of penetration, help to approximate the highest point of penetration for a mandibular anesthesia technique.

Often called the “Wide Open Technique,” the Gow-Gates Nerve Block requires the patient to remain open in a wide-enough position during the injection to permit exposure of the anterolateral surface of the neck of the condyle as the point for boney contact prior to injection as well as two to five minutes post-injection to ensure adequate saturation of the mandibular nerve for comprehensive anesthesia.

Contraindications to this injection are patients who are unable to open wide, patients with TMJ disorders and/or trismus, and patients whose large flare of the tragus indicates a wide flare of the condyles and subsequent prevention of the needle from contacting bone prior to anesthesia delivery.

In addition, providers should be cautioned that onset of anesthesia is slower than that of other injections; it can take anywhere from five to 10 minutes. Many new clinicians trying the Gow-Gates Nerve Block may prematurely deem the injection unsuccessful without waiting the appropriate time to permit adequate saturation of anesthetic to the nerve membrane.

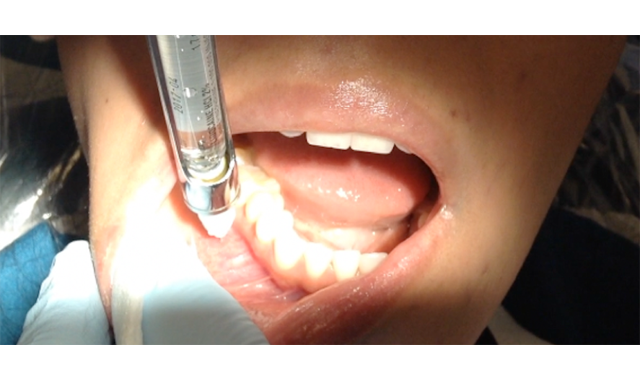

3. Vazirani-Akinosi Closed Mouth Mandibular Block

Perhaps one of the most frustrating events during the delivery of mandibular anesthesia is the combination of a curious tongue and a patient who thinks “open” means “slowly close down during the injection until you’re nearly occluding on the barrel of my syringe.”

As discussed with the previous technique, many times the patients’ ability to open widely is required. For patients whose tongues are so large you struggle to visualize the pterygomandibular raphe, or for patients who present with TMJ disorders or limited opening abilities, the Vazirani-Akinosi technique is an excellent choice in the achievement of unilateral mandibular anesthesia. Of note, patients who experience trismus or severe bruxism in which needle penetration through overstimulated muscles may render post-injection soreness are excellent candidates for the closed-mouth technique.

Another brief history lesson: In the 1960s, Dr. Vazirani published about a closed mouth technique and in the 1970s Dr. Akinosi reported an identical technique aiming to achieve successful block of the mandibular division (V3) of the trigeminal nerve. The technique is now named the Vazirani-Akinosi Closed Mouth Block to honor both doctors who devised and published the technique.

The block itself thoroughly anesthetizes the inferior alveolar, incisive, mental, lingual, and mylohyoid nerves with one simple needle penetration placed laterally to the mucogingival junction of the maxillary teeth on the side to be anesthetized. Barrel orientation is considered parallel to the maxillary occlusal plane upon requesting the patient to close after retraction, and depth of penetration is achieved at approximately 25 mm into the tissue for an adult patient. Bevel orientation is the only concern as it is imperative that the bevel point toward the midsagittal plane (away from the ramus) to minimize needle deflection during penetration.

This block technique not only provides adequate anesthesia for restorative, periodontal, and/or surgical techniques of a mandibular quadrant but also for unilateral temporary motor paralysis for trismus patients with decreased opening capabilities.

4. Mandibular Infiltration with Articaine

As I was preparing my patient for anesthesia delivery prior to a filling placement, I discovered an interesting phenomenon. This was discovered as I diligently placed the topical anesthetic just under the mesiolingual cusp of the maxillary second molar in preparation for the delivery of a Gow-Gates nerve block when my patient asked to confirm the tooth being worked on today.

Typically I would take this as an opportunity to educate the patient on the placement of the inferior alveolar nerve, etc. when I realized that my patient was receiving care on a mandibular premolar. You see, to my patient, my high and posteriorly displaced topical swab left my patient questioning if I knew which tooth was being worked on that day.

We are trained, as providers, to deliver block anesthesia for mandibular teeth, which often leaves us utilizing questionable, inconsistent, and unsuccessful injection techniques. Realistically, the delivery of higher quantities of anesthesia into a higher risk site of penetration for a regional block simply doesn’t make ethical or clinical sense.

The technique of delivering 4% Articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine at the apex site of the mandibular tooth to be treated permits a direct, effective, and comprehensive approach to single-tooth anesthesia. Additionally, this injection technique boasts an 87 to 88 percent success rate, particularly in the presence of symptomatic or irreversible pulpitis in mandibular teeth.

Without consistent injection failure, troubleshooting, or complications, the use of Articaine for mandibular infiltration provides a safe and effective alternative for single-tooth anesthesia, which is an excellent choice for patients who are receiving localized care during their dental appointment.

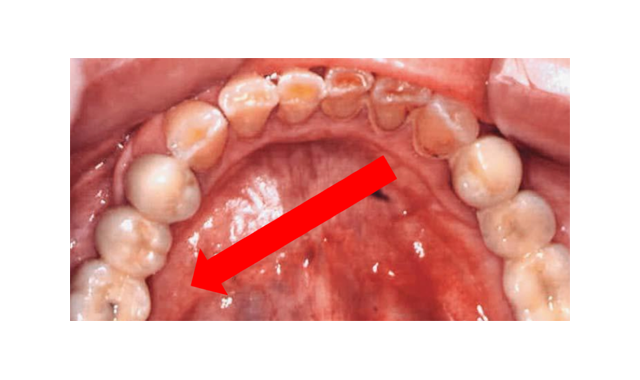

5. Mylohyoid Nerve Block

Often, delivery of a mandibular block results in partial anesthesia. Many providers find frustration when achieving profound buccal anesthesia with subsequent inadequate lingual anesthesia. At this point, many providers opt to re-penetrate to simply deliver anesthesia for saturation of the lingual nerve.

Of note, the lingual nerve is the most common nerve affected during paresthesia cases and risks of paresthetic complications increase with supplemental penetrations through and anesthetic saturation of the lingual nerve. Therefore, it’s important for providers to consider safety and risks when attempting to achieve supplemental lingual anesthesia.

In approximately 60 percent of inferior alveolar injection techniques, accessory innervation is provided by the mylohyoid nerve. This overwhelming statistic means that providers who frequently deliver inferior alveolar nerve blocks experience anesthesia failure, not due to poor injection technique, but rather due to anatomical considerations.

The mylohyoid nerve is typically anesthetized during the delivery of the inferior alveolar nerve block but is often obstructed by anatomical landmarks such as the pterygomandibular fascia or the sphenomandibular ligament. Providing anesthesia to the mylohyoid nerve effectively blocks sensation to the mylohyoid muscle and the anterior belly of the digastric. Essentially, the next time your patient gives the “iffy” face and states, “I can still feel my tongue,” please consider the mylohyoid nerve block.

With ease of delivery, the mylohyoid nerve block is completed by retracting the tongue (good luck!) and penetrating below the apex of the most posteriorly placed tooth on the side requiring anesthesia. Upon gentle contact with bone, anesthetic is safely delivered to provide supplemental lingual anesthesia without high risk of failure or complications.

The mylohyoid nerve block is an excellent alternative injection technique for most patients. Of course, moving around large mandibular tori may be the one contraindication to the delivery of this injection.

Conclusion

I hope that this article has provided insight into the incredible world of available alternative local anesthesia injections that can benefit the provider and patient. Please know, however, that there are plenty of other anesthesia techniques available to the provider.

Considering delivery of a V2 injection will provide hemimaxillary (unilateral anesthesia of the maxilla) anesthesia for quadrant dentistry. The Loma Linda Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block technique utilizes a short needle to achieve unilateral mandibular anesthesia while many currently utilize a short-needle IA technique to approximate the inferior alveolar nerve’s location.

Techniques such as the TuttleNumb Now technique permits single-tooth anesthesia with short onset and profound anesthesia. Providers also utilize techniques like the Periodontal Ligament Injection, Intraosseous or Intrapulpal Injections for single-tooth anesthesia.

Additionally, injections such as the Intraseptal technique can provide an alternative to uncomfortable palatal injections.

Finally, advances in research of local anesthesia like a nasal spray can provide alternative delivery options for providers.

I encourage you to consider attempting the injections you feel comfortable with or taking an alternative local anesthesia course to familiarize yourself with anatomical and technique-sensitive considerations. Having additional injections to add to your tool belt will ensure a more confident, skilled, and effective clinician in achieving profound local anesthesia.

Happy injecting!

References

Bassett, K., DiMarco, A. Naughton, D. (2015). Local Anesthesia for Dental Professionals 2nd ed. Pearson. Lakewood, Washington. ISBN: 978-0-13-307771-1

Blanton, P.L., & Jeske, A.H. (2003). Avoiding complications in local anesthesia induction, anatomical considerations. Journal of the American Dental Association, 34(7), 888-893.

Gow-Gates, G.A., & Watson, J.E. (1977). The Gow-Gates mandibular block: Further understanding. Journal of the American Dental Society of Anesthesia, 24, 183-189.

Krall, B. (2008-2009). The Loma Linda Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block Technique, from Loma Linda University School of Dentistry, the Local Anesthesia Manual.

Malamed, S.F. (2013) Handbook of Local Anesthesia 6th ed. Elsevier, Evolve. St. Louis, Missouri. ISBN: 978-0-323-07413-1.

TuttleNumb Now. Acquired From: http://tuttlenumbnow.com. Accessed on February 26, 2018.

Related Content: